an interior landscape1

… I would be nobody, that is, myself.

Charles Brasch was born into a wealthy, cultured family (his great-grandfather was Bendix Hallenstein of Hallenstein Brothers), and his origins were to prove both a spur and a source of tension throughout his life. He lost his mother early: ‘Her death was the first blow to shatter the family. It also, I see looking back, ended my childhood proper, shortly before my fifth birthday’. We are introduced in the early chapters of Indirections to a world which revolves round four related (Hallenstein) families, living in London Street in Dunedin in the early part of the century, including their housekeepers, gardeners, nurses, summer visits to Karitane, sedate grand houses and lifestyles, and, unmissably, Grandfather’s magnificent classical garden (‘From the time my mother died until I left school the real centre of my life was Manono, Grandfather’s house. So long as he lived it remained the foundation of my life’). Willi Fels, Grandfather, resides as mentor at the centre. With him the narrative opens and closes (his death in 1946). He personifies a habitat in which Brasch develops early a sense ‘of the beginninglessness of things, of their permanence whether they are present or not’.

For poetry comes to mean everything that is Charles Brasch:

The sense or conviction that I was, that I had to be, a poet, and must persist and hold out until other people recognized it too, had taken possession of me and was not to be shaken. If I was not one, then I had no real existence, and no reason beyond habit for going on living.

The direction to be followed is – as the epigraph has it – ‘By indirections’. Beyond family history, beyond the surrounding natural and regional splendour, and the various individuals woven into the narrative, there runs the deeper thread which is Brasch’s developing realisation as poet and man of letters. Only after the war, when he returns from England with the purpose of founding the literary journal Landfall, is that other foothold firmly established.

So what is to be made of all that occurs between? How does mundane life assume extraordinariness? From the opening chapters an internal imaginative formation is the imperative:

I grew to know most of the country about Dunedin, in all its variousness. It impressed itself on me so strongly that it seemed to accompany me always, becoming an interior landscape of my mind or imagination, unchanging, archetypal, the setting of what I read about as well as all the life of the present. The shapes, textures, scents, sounds of all its landscapes grew with into me and grew with me.

These impressions become a means of self-generation. Brasch’s personal susceptibility in their presence sustains his sense of life, eventually becoming it. On an earlier brief return to New Zealand, in 1936, he visits Queenstown Park, and the recounting of the visit is beautifully rich in its suggestion:

And those winds and waters worked on me, I thought, to the same intent, to make of me something I could not foresee; I was to leave myself open to them, not to let myself slip now into some pre-ordained fixed stock shape, my responses ordered, mind and sense all but closed: to take whatever chance might come; not to play safe. To be like the Park itself, a jewelled leaf, long, narrow, finely drawn, thrusting into the cold waters of the lake, nearly all shore surrounding a mere spine of rock and earth and that tall prow-wedge of trees, warm in their darkness, rocking, soughing.

The narrative, in a revealing sense, undervalues itself: ‘Prose is the medium of those who have not been granted the gift of poetry’. These are, the Foreword tells us, ‘recollections that I was not able to shape into poems’. A willing secondariness – or formation – extends across the entirety of the book, at times almost overly so. It is as if the author, reticent in case anything should be undervalued, travels

with too extreme a watchfulness, absorbed by every nuance of colour and shade. This suggests his being unsure himself about what boundaries should be placed on the experiences recounted, until their imaginative transformation has taken place.

The Egypt and America chapters, for instance, while fascinating, are largely extraneous to the other journey that Brasch undertakes – in an account which, we are told in Bertram’s preface, has already been trimmed to half the original length! Relations appear sometimes in disconcerting proportions. Brasch’s impressions often stop at a person’s ‘sweet nature’ or at couples who ‘loved each other almost as soon as they first met’. Wili Fels, with his ‘many-sided,… settled and permanent’ interests, and James Bertram, a close confidant since childhood, appear as larger-than-life sheltering figures, who are open to the possibilities of the imagination; whereas others, especially his father, Hyam Brasch, are viewed as indifferent or hostile. About others there is a curious reticence. Of a vague love affair based on ‘a hopeless long-drawn-out devotion’, which left Brasch feeling devastated, we are told only that

I had longed for a complete impossible union of souls and bodies, physical and spiritual in one, a living together of perfect openness, absolute trust, total sharing and reciprocity. When it was over, I knew I should never love in that that way again (let alone be loved), and never find what I sought; knew that such entire mutuality in love is not to be hoped for; that I was alone and would always be alone.

Similarly, in a chapter bearing her name, sister Lel (Lesley), whom he helped nurse through a long and debilitating illness, but otherwise with whom little is shared in common, is hardly a presence.

From his earliest years he recoils instinctively away from expectations that he will eventually take up an expected commercial or legal career. When a young schoolboy home from Waitaki on holiday, and his father returns after a day’s golf, ‘flushed with success’, a grilling is sure to follow –

His first question, an almost invariable one, on weekdays or at week-ends, I anticipated with hollow heart; this was the question that would be put to me at the Last Judgement, and the result was pre-ordained; then as now I would be found wanting. 'Well, and what have you been doing today?' My father's tone was cold, critical, disappointed, disapproving. He had been out in the fresh air, taking exercise, showing his skill, mixing with other men, proving himself in the world. This was what was expected of a man, as a good member of society,

Charles feels defeated, hopeless, his confidence undermined. Thereafter, any form of external authority encountered risks filling with mistrust, stubborn resistance. Not truly a welcome part of the world, he struggles to prove himself:

The question struck at some deep-seated sense of guilt in me which once wakened left me raw, heavy with shame, incapable of defending myself. It was not that I was made to look wrong in my own eyes, but that I was proved wrong In the eyes of the world, of all external authority, as represented by my father.

And so he retreats further into himself. Through a desire to build an ideal accepting world, he turns increasingly to poetry and the imaginative arts. At Waitaki, especially with Bertram and Ian Milner, he develops friendships which are to sustain him throughout in his resolve to be a poet.

However, the relatively happy time at Waitaki is cut short when, in 1926 aged seventeen, he receives a letter from his father asking whether he would like enter Oxford the following year. In consenting, the course of the son’s future life is altered. His family ties, his love of Central Otago, so vividly related in the Southern Lakes chapter, remain with him, but in the remaining chapters of the book, which deal mainly with time spent in and England and surrounding, we witness a growth In European temperament in the burgeoning poet.

The same reticence found in the treatment of personal relationships is evident in his decision to be a poet: ‘That I had to be chiefly a passive onlooker left me, much of the time, feeling helpless, guilty, stifled with frustration, fiddling while Rome burned. And I could not even fiddle well. Yet I thought somehow I should one day make a noise in the world, a noise of my own’. Later, he reflects: ‘I used to think I had no identity at all, but if that were so I would be unaware of having none because there would be no I to be aware’. Beset with introspective feelings of utter insecurity, his surrender to the muse is, if personally irrevocable, not entirely submissive either. A lack of directness, remaining aloof, these his devotion required – though at a cost. The narrative figure who speaks through the memoir is one inclined to negation, emotional detachment. When Iris Wilkinson (Robin Hyde), desperate and with suicidal thoughts, turns to him for ‘closer comfort and reassurance’, he recoils. His explanation: ‘But physically she repelled me; I could not respond more than in friendship’. The attempt to become divested of self is at once intensely personal and without personality, abidingly private and yet beyond the reach of certain intimacies.

Brasch commits to becoming; what comes into him he is. At this inflexion point, an idealised vision may threaten – or require – personal dissolution: ‘I began to see that the only way In which I could save myself from dissolution in the bewildering formlessness of the time was to draw distinctions, establish small islands of meaning, and so gradually build up a living centre of my own’. His ‘long tedious painful apprenticeship’ gradually resolves itself against a backdrop of a turbulent Europe through the ‘thirties and ‘forties; a time during which, for Brasch and others, the civilization in its entirety seems to vacillate between social renewal and a headlong rush towards self-destruction.

Under the Influence of Plato and Shelley, Krishnamurti and Buddhism, among other things, the developing poet’s ‘bids at purity’ gradually lead to a realization that real purity lies beyond the Immediate reach of the body and the world: ‘The purity I believed I longed for failed to distinguish properly between what goes in at the mouth and what comes out of the heart’ (an anatomically awkward metaphor). In European, especially Italian, art, he discovers transcending beauty:

The power and powerlessness of art - its power to transform inward life without apparently touching the life of the outer world - this troubled me constantly. One must want, as an artist, to transform the world both within and without, to create an Ideal beauty which would redeem ugliness and evil [a further convolution?].

Italy reveals the things he is to treasure most dearly:

Falling In love with Italy on my first visit, I found further reasons for loving it on each later visit, more to interest and excite and satisfy me. It seemed to anticipate, and to answer abundantly, all the urgencies springing up in me; the hunger for beauty of every kind, for proportion, for meaning; the need to understand. Involvement with Italy also brought me closer to Grandfather and my aunts, to all that Manono stood for. The very sound and rhythm of the name Italy rang and sang with its concentrated meaning.

His time in Europe is spent at Oxford, at Tell el Amarna in Egypt, where he works as a kind of unpaid archaeological cadet, in Greece (and elsewhere) for a brief holiday, at Little Missenden Abbey, where, under the tutelage of Mrs Lister-Kay, he teachers ‘difficult’ children, and in London, where he works during the war as a fire-watcher and junior assistant at the Foreign Office. During this time, he rejects the option of direct political action and, by the time he returns to New Zealand to found Landfall, his commitment to indirect action (transformation) is clear:

Suddenly appalled and overwhelmed once again by such a prospect [of continued war], for I had been indulging the hope that peace really meant peace, I asked myself whether it was possible to continue to live a private life pursuing private ends, or whether a more public and political life was not demanded, a deliberate effort to try directly to bring about a better world. The question dogged me. But there was only one answer: the world must go on In all its complexity: political action is never a complete response to earth's disorders, and as a way of life it can be for the few only. For most people an indirect way is inevitable, and probably far more effective.

During this time he meets with friends Glover, Bertram, Milner and Jack Bennett, to discuss with them the prospect of establishing the new journal, envisaged as ‘a mature professional Phoenix’. Committed to building a better world, he decides, after the war, to return to this ‘drab’ ‘formless’ land, which shuns excellence and has only recently given first signs of ‘coming to be’, there to settle and establish Landfall. His poems of the war years, his best yet, he tells us, point unmistakably in that direction: ‘It was New Zealand I discovered, not England, because New Zealand lived in me as no other country could have, part of myself as I was part of it, the world I breathed and wore from birth, my seeing and my language. England, deeply as I had come to love it, was not myself in that way and could not be’. Already in his middle thirties, he sails back to the country from which he had formerly escaped and which he will always view, in some ways, with misgiving. As editor of Landfall from 1947 to 1966, he will bring what he has learned in Europe to the fore in helping to foster this country’s barely embryonic intellectual and literary life.

+

... the total order of being is a unity, a dance, a cosmic drama.

Much of the struggle to become a poet and find meaningful work is resolved in the period covered in Indirections, which ends where Landfall begins. The Landfall years are more settled; and it is from these years that the editor of The Universal Dance, J. L. Watson, has made a selection of Brasch’s critical writing. The book complements and is a continuation of the memoir, bringing similar concerns into a more formal, public forum.

However, it is not for its critical acumen or deft insight that Universal Dance repays our attention. Longer pieces like ‘The Structure of Verse’ and ‘Modern Poetry’ come across as somewhat elementary and old-fashioned; although brief reflective passages dealing with Baxter and Eliot are quite incisive. Overall, the book is guided by the values of the past, embodied especially in the English literary tradition. In this respect, the inclusion or selected Landfall ‘Notes’ offers more than mere ballast in demonstrating Brasch’s immediate tenor of thought as editor and critic.

Indeed, his aesthetics vision arrives already well-formed in the first ‘Notes’ of March 1947. Between this and the 1965 lecture, ‘Present Company’, there is a retracing of the same process of the person of the artist’s subsumption into art. Brasch describes the conditions out of which art arises. The arts, he avers, are not to be viewed in isolation:

They are products of the individual imagination and at the same time social phenomena; raised above the heat and dust of everyday life, and yet closely implicated in it. Any serious consideration of them is bound to involve an inquiry into their place in society and the social functions which they fulfil - what part they play in life, what use they are. This in turn must lead sooner or later to questions about society itself and what it exists for, and, eventually, about the nature of man.

What begins as a consideration of the social function and usefulness of the arts quickly leads to a questioning (through them) of society and of the nature of man. The central theme to which the arts always return is ‘human life as such’; they are its ‘interpreters’, they display its ‘inexhaustible variety’, and more importantly, they ‘relate’, they ‘speak a language of reconciliation’. Aesthetic and human values coalesce: ‘To relate: that is one of the chief social – and spiritual – functions of the arts’. Landfall’s purpose, Brasch avers, is ‘To rediscover a just relationship between the arts and men’s other activities, and a single scale of values to which all can be referred – that must be the constant aim of those who care about them’ (my italics).

The process as outlined can perhaps best be depicted in the form of a triangle, the base corners of which represent ‘individual imagination’ and ‘social phenomena’. Lines from each of these reach up to form

an apex, and this represents works of art produced out of the relationship between the individual imagination (the artist) and social phenomena, All three elements are circumscribed by a line that touches each corner and binds them within a shared circle – ‘a single scale of values’.

Brasch continues:

[The arts] are essential to any civilized society, because it is only through them that the everyday activities in which men are immersed can be felt (and feeling in this sense carries the unmistakable force of conviction) as belonging to to some greater order whose significance is the ultimate sanction of society. Without them, society would in the long run be intolerable, because meaningless - its meaning (if any) could not be communicated.

Only through art, we are told, can society be considered tolerable, meaningful. Only through art can people feel with conviction that there is ‘some greater order’ in which everyday activities are found to have meaning. This order, Brasch continues, ‘may not be definable in terms of any of the religions’, for art and religion are ‘distinct and autonomous’ spheres, and what Brasch is drawn to instead is a spiritualised creative sensibility, of the kind artists like Goethe possess:

Yet what Christian writer since Goethe has given men any sense comparable to his of the greatness and goodness of life - life as a divine gift, of the value of human striving, the rightness of the whole immense complex effort of civilization? Who can inspire them as he can with the will and courage to go on, the hope of making something of the world after all, in spite of weakness and error and guilt? (Landfall 'Notes', 'Goethe')

This is why Goethe, Rilke and Graves, are so prominent in The Universal Dance. They each have something of this ineffable spiritual quality about them. They create ideal worlds. In the end, as Brasch suggests in his retirement article, ‘Twenty Years Hard’, it is from perspectives of the finest works of literature and art ‘that one can form the broadest and most philosophical view of life, human, animal and divine’.

What then, we may inquire, is that order to which the single scale of values points? This Brasch describes in a later set of ‘Notes’ in 1954, when he speaks about the gradual coming of age of a society as it begins to live by an imaginative order of its own. I quote him at some length:

In older countries, where an imaginative order already exists, new works of an and literature need only embellish or extend or re-define that order. But in a raw colonial society much more is demanded of them; they have to create order for the first time, in a wilderness that is without form and very nearly void. Every work with even the mildest charge of imaginative vitality therefore assumes for the time being capital importance (which it will certainly lose later) as a new cell in the body of the embryo order.... The struggles of literature and art in a young society, however confused, are never without purpose; they are always governed by that obscure urge to create an imaginative order, without which, all material order, the everyday life of society, is empty and barren. If artists begin by exploring, in the narrowest sense, place, time, and identity, it is because they have to be sure of firm ground under their feet to start with. Later they can go on, reaching out towards the general and universal where imagination has greater scope, to construct an intellectual and spiritual order, which is the ultimate need of an adult people and may help to satisfy its hunger for perfection.

Because we in New Zealand (at the time) had only ‘four walls and a roof over our heads, the skeleton of an imaginative order’, Brasch argues, a double standard of criticism was for an interim period a necessary measure. The primary (measuring) standard is

distilled from the master English tradition. Accordingly, in ‘Present Company’, the touchstones of excellence are decidedly European and New Zealand and its artists hardly figure. The derived double standard takes into account the fact that new works of art must ‘create order for the first time’ and therefore are of ‘capital importance’; eventually they will lead to the establishment of ‘an intellectual and spiritual order, which is the ultimate need of an adult people’.

Art is not necessarily presented as itself that self-substantiating ideal order, but for Brasch it is the only means by which it can be pointed to and communicated. The single scale of values which encircles the triangular relationship mentioned above is incorporated within an order on which it depends and from which it can be extrapolated. The imaginative order subsumes society though society has access to it through the arts. And the arts subsume social phenomena and the individual imagination though they depend for their existence – their materials – on the relationship between them. Graves, with whom Brasch feels a special affinity, is spoken of as one who speaks ‘to all who understand that imaginative experience, of whatever kind, is the most real form of experience, and the only one that can redeem our lives from triviality’. The essay concludes:

Only those can perform it who have a vocation for it, a calling to it, which is not under their control or that of society. All we can say, all we can hope, is that those who are so called will submit and obey to the best of their powers, according to the state of grace they are in; and that society or part of it, part acting for the whole, will be in a condition to listen and take heed and be revived. ('Robert Graves')

For Brasch, a poet by will (‘I had to be a poet’), the poet takes to themself those special functions and powers to which society has traditionally made highest claim (God, grace, civilization). ‘Perfection of the work, if you take all the implications of that phrase, is for the artist perfection of the life’ (‘Conditions for Literature’).

In the same essay on Graves, we see that the critical vocabulary applied by Brasch is quintessentially romantic: ‘springs of poetry’, ‘great powers’, ‘undivided poetic personality’, ‘whole of human experience’, ‘utterly necessary poems’, ‘profound truth’, and so on. Accordingly, society (art’s material source) is berated as antipathetic to the arts, to its very capacity for hope, self-renewal and insight. Russian communism is slated for its powerful inhibiting effect on the arts; while in ‘Conditions for Literature’, Brasch vilifies ‘that ugly and sinister dream world of drink and betting in which too many New Zealanders seek escape from a life which the pressure of conformity has helped to make intolerably drab and empty’.

In ‘Present Company’, the New Zealand education system gets more than its fair share of scolding: ‘you leave [students] a prey to all the invitations of commercialised society in the seedy, permissive, insidious forms which they take in this country, and from which no one now escapes’. This is something different from social criticism per se: ‘In short, without education, memory will fade, and poets, painters, and musicians disappear’. Brasch speaks with total certitude and authority because his knowledge of art is entirely embracing and self-generating: out of this conviction he launches an attack on the education system without this being exactly an attack on the education system, but rather on all forms that arguably inhibit or compromise aesthetic transformation. Elsewhere he speaks of the poet’s poem as ‘an approximation to his ideal poem’, where the poet has ‘an idea of the kind of poem he is writing, an idea almost in the Platonic sense, one which is present in his mind, yet not in words; and what he has to do is to translate that idea of the poem into an actual poem, into words’ (‘The Structure of Verse’). Everything intimates and dwells in ideal form.

And ‘Present Company’ elaborates that ideal most fulsomely. The artistic process is simultaneously a creation and discovery. It can be depicted as follows:

material and its

potentialities ------> discovery ------> creation

('featureless block ('to see') ('set it free')

of potentiality')

Using Michelangelo to illustrate, Brasch describes the relationship between creation and discovery as one in which ‘The figure was without doubt there, hidden in the stone, had always been there potentially, but it took Michelangelo to see, that is discover, it, and to set it free or create it’. Discovery is ‘the finding or revelation of an existent fact or truth which the artist recognises and acknowledges’. In this discovery of what is already there, the artist makes of it something that is new, transforming it, while leaving it unchanged, and presenting us with a newness – in words, stone, pigment.

Here the criticism folds onto itself. For what had been discovery of an ‘existent fact or truth’ may in turn, we learn, have deficient, or at least not-yet fulfilled; all the while a definite relationship between art and the physical world exists: ‘there is no unbroken bridge from the apparent sources of a work of art to the work itself. A logical and real gap exists, and it is in that gap that we must place the flash of lightning in which the work of art was conceived’.

The discovery of what exists as potentiality in the physical and temporal world (‘raw materials’) becomes, through this fold [sleight], the discovery instead of the world that is created by art:

It is in creating the world that we discover the world and ourselves in it, and what we discover is something that exists, that must have existed always, because we are discovering the nature of the world, of the cosmos, of being itself.

Such is the folding and refolding of reality that art brings into play imaginatively:

The discovery that we make in contemplating a new work of art is above all a discovery (as I said before) of the nature of the world. The work confirms our primary understanding and experienced knowledge that the world is of such a nature; it does so because it conforms to the nature of the world, which is itself, in a thousand variations different in scale, that of a work of art, a dramatic presentation, a ritual play.

The ‘discovery that we make’ is of a new work of art and in discovering it we discover ‘the nature of the world, which is itself, in a thousand variations different in scale, that of a work of art’. ‘Nature’, ‘the world’, ‘reality’, are transferable terms that, like ‘creation’ and ‘discovery’, shift about in an interplay of crossings-over of what is and is not.

As a result, physical reality appears as ‘exceedingly miscellaneous raw material’, everyday communication is depicted as ‘the confused babel of everyday language’, and we are obliged to share in Brasch’s astonishment that art should seem to deny all contingencies and rise ‘not only in ordinary peaceful life but amid the din of conflict and the stench of death, through wars and famines and revolution’. Poetry is the type of the arts, the perfect art form. The poet makes, ‘if not exactly something out of nothing, at any rate something new, which was certainly not there before’. But the qualification is immediately undercut: ‘If poetry is making, and making in an unqualified, absolute sense, then one can perhaps draw the conclusion that only what shares the nature of play, of the dance, is real’. In light of this a great work of art by an Englishman ‘changes the nature of England’ and ‘Douglas Lilburn has given us the first New Zealand sounds and so begun a new language’. Where it all leads is to the overcoming of the material and temporal world. The world which has served as the seed to the ideal imagined world of the arts its itself absorbed and lost in it.

The gross solidity, what Lear called the 'thick rotundity' of the world, the heavy and dreary world of things, machines, institutions, with its seeming immovability and lastingness, is an illusion which the arts implicitly deny. Their whole effect is to liberate us from the static and dead, which is the contingent to draw us into the stream of necessity, the continuities in motion and change of the rhythms of reality.

Relieved of its substance, the world becomes a place of play, dance, The Universal Dance.

notes

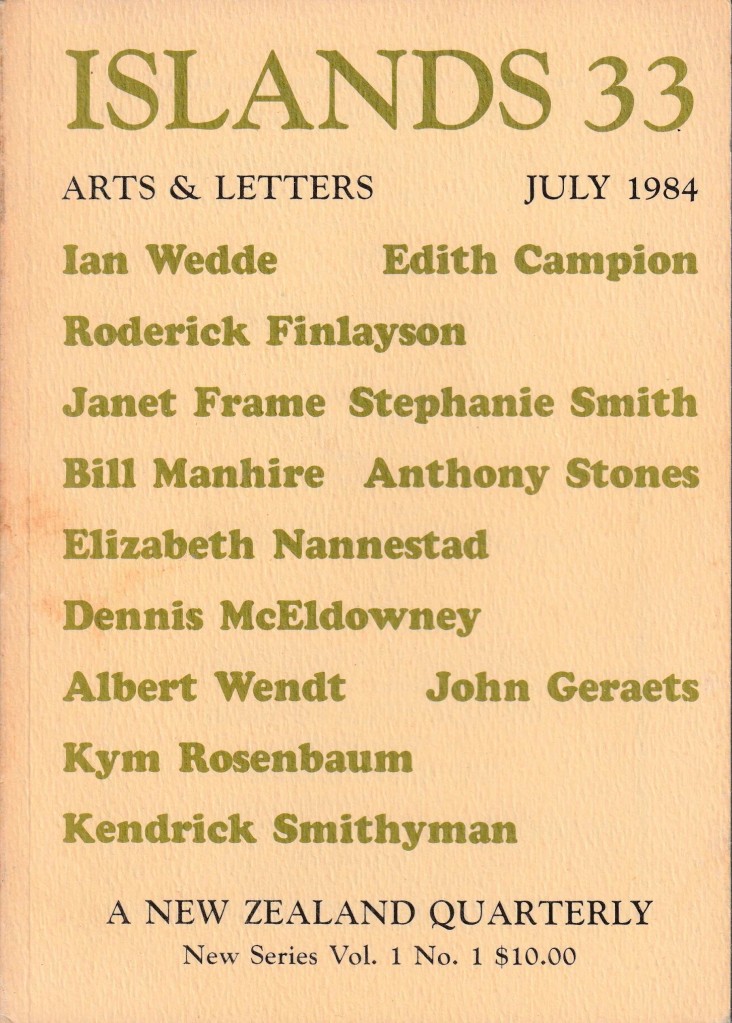

- Charles Brasch, Indirections, A Memoir (OUP, 1981) and The Universal Dance (UOP, 1981). The essay was prepared at the editor of Islands’ invitation, in the same year. ↩︎